Email bombing: what you need to know

How email bombing works Email bombing involves overwhelming a target’s inbox with an excessive number of email messages in a very short time. The...

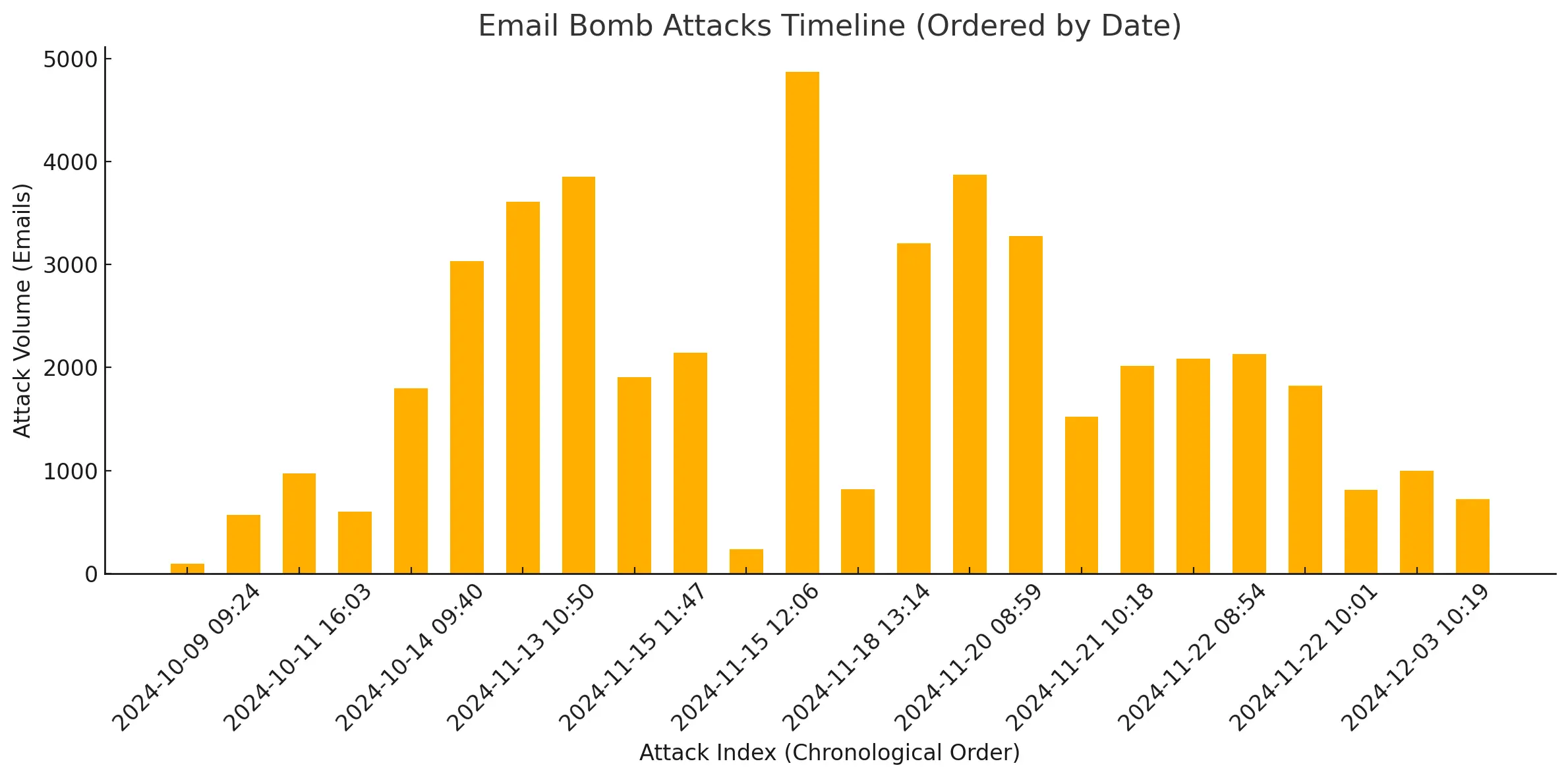

On November 13, at exactly 10:50, Lars’ day took an unexpected turn. Within 63 minutes, he received more than 3'600 emails from newsletters and services he didn't recognize. The sudden inflow of unwanted email messages disrupted his work and set off alarm bells across his company. What seemed like a technical glitch at first quickly escalated into a serious security concern, leaving Lars and his team scrambling for answers. Lars (not his real name) is an Executive Officer of a fintech company and was just hit by an email bombing attack. Email bombing attacks rose to prominence in 2024 and are challenging to mitigate.

Over the past two months, we analyzed 24 such incidents across six organizations, uncovering patterns and insights that shed light on how these attacks work and how they can be prevented. Here’s what we found.

The first attack in our dataset occurred on October 9, 2024, with the victim receiving only 95 emails spread over one hour — a fraction of the average number of 1,957 emails per bombing in our dataset. The low volume and the fact that it's the first attack we observed suggest that the attackers may have been testing their setup before scaling their campaign. We see a similar, low-volume attack about mid-campaign on November 15, which could point to another test (or maybe a trial with a different service but more on that later).

Over nearly two months, the bombings targeted 17 individuals across six organizations, delivering close to 47,000 emails. The largest attack delivered 4,847 emails in under two hours, while the most recent bombing in our data, on December 4, lasted just over an hour and delivered 719 messages. At this time, we can only speculate why there is a gap of almost one month between mid October and mid November.

The attackers targeted different industries, including retail, technology, and manufacturing, with no discernible pattern. What stood out was that victims were typically individuals with roles involving external visibility — it is likely that their email addresses were publicly accessible or easy to guess.

Interestingly, no IT or IT security personnel were targeted, suggesting a deliberate focus on less technically equipped employees. In most organizations, only 0.1% to 1% of the workforce was affected. We believe that the attackers likely chose a selective approach to not trigger certain volume-based thresholds installed in their targets' email security.

The email bombings in our sample exhibited consistent patterns but also revealed some variations in duration, volume, and tactics.

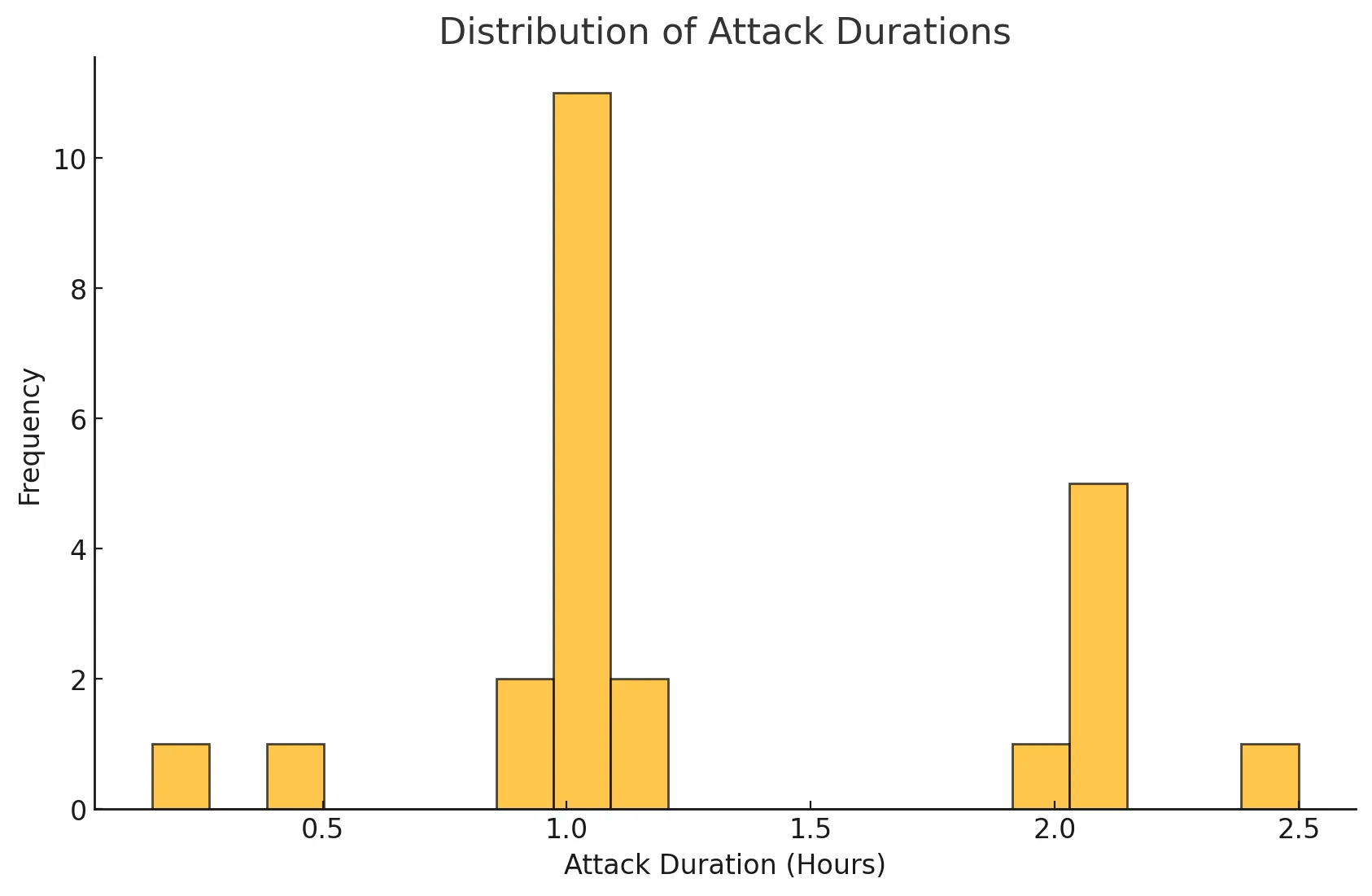

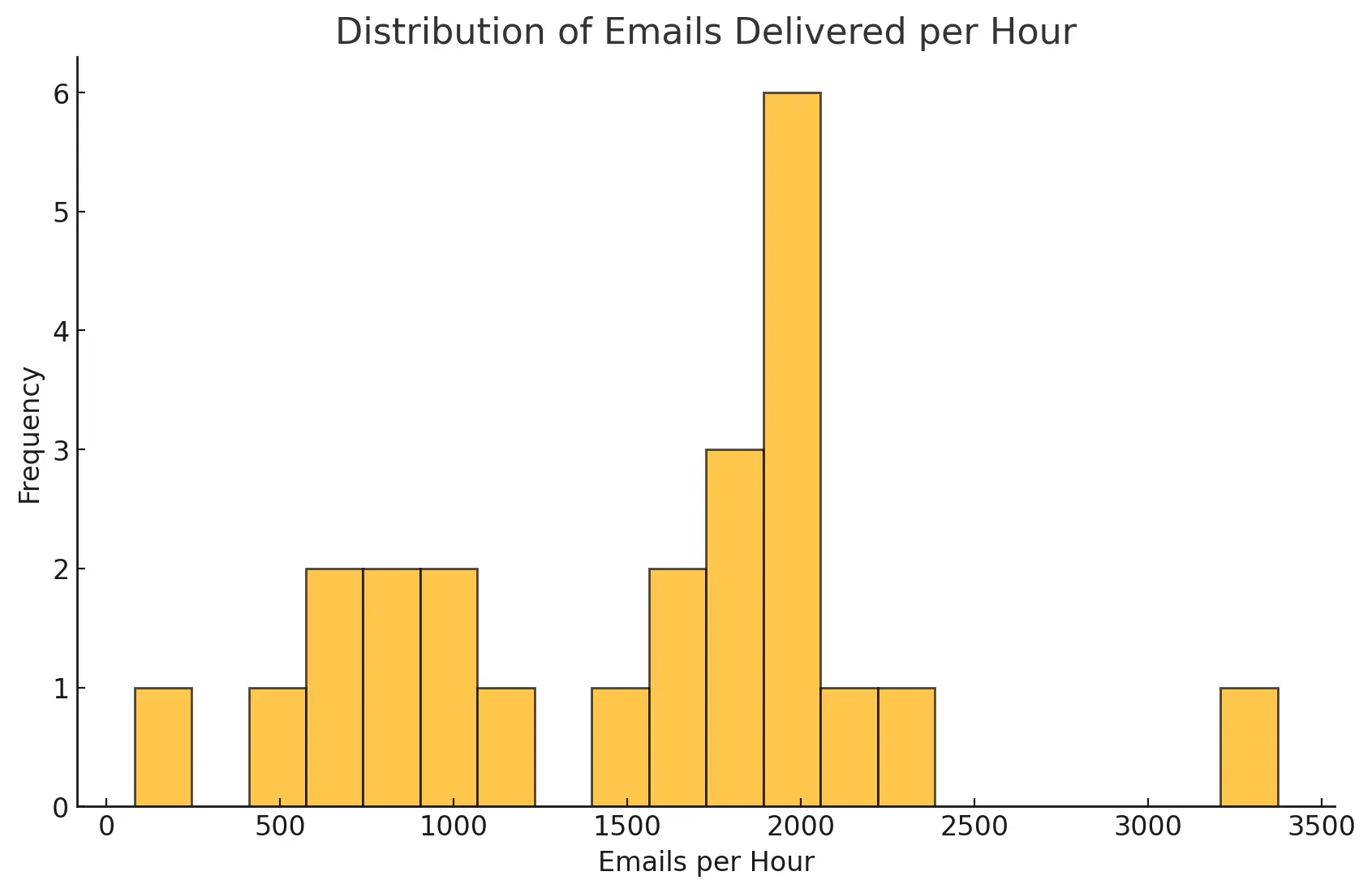

Email bombings were short but intense. On average, attacks lasted 1.3 hours. 15 attacks lasted around one hour, seven hit or exceeded the 2-hour mark. Delivery rates started at 600–1,000 emails per hour in October and surged to over 2,000 emails per hour in November. The data suggests these campaigns were sold as hourly services on underground forums. The one-month break and subsequent surge could also be linked to a relaunch of a known email-bomber-for-hire service.

.

The average attack delivered 1'516 emails per hour. The minimum was 81 and the maximum 3'387 emails per hour. Most attacks delivered between 900 and 2'000 emails per hour.

Victims experienced varying levels of disruption: 12 of them were targeted once, three were hit twice, and two faced three separate attacks.

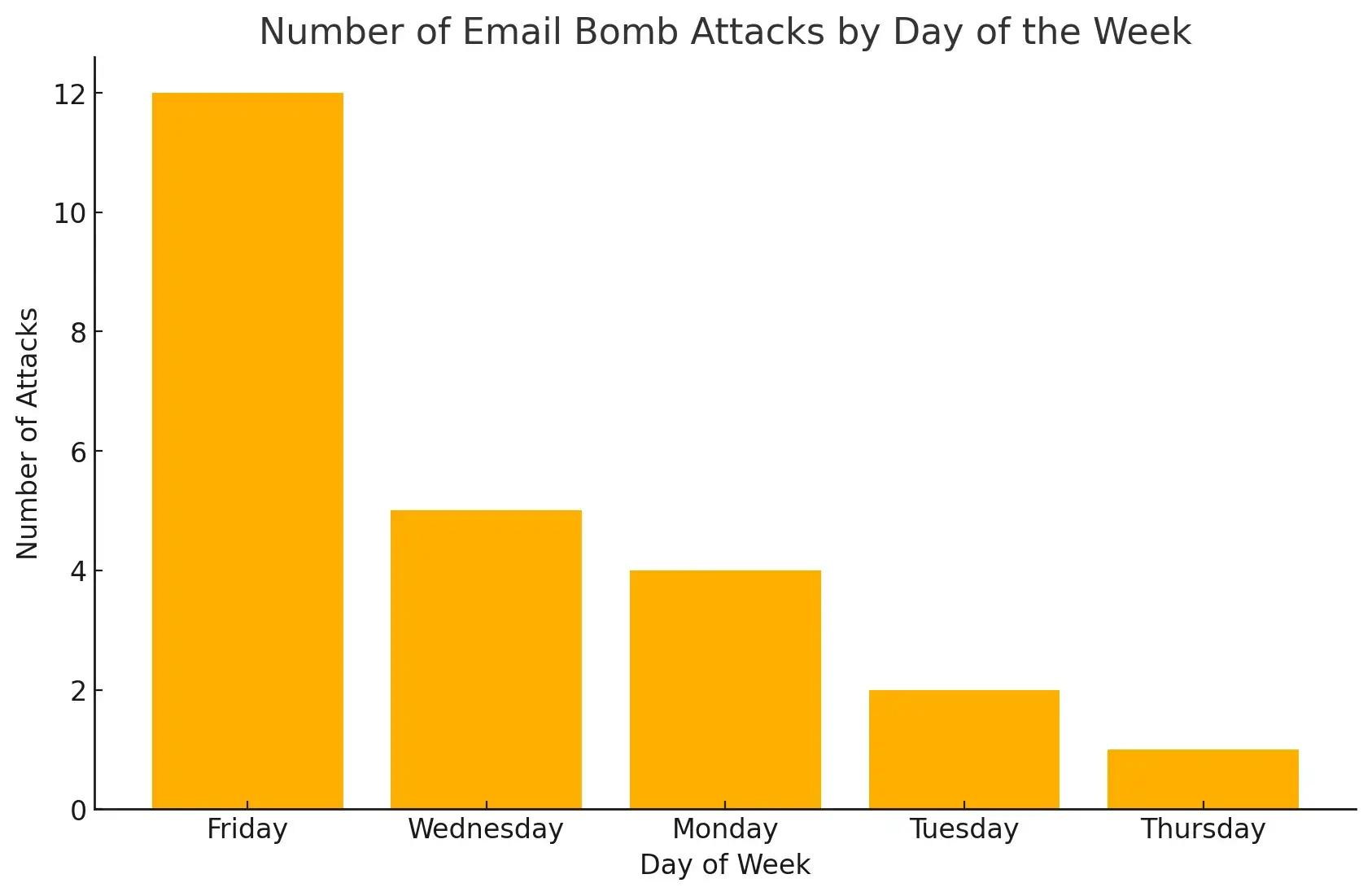

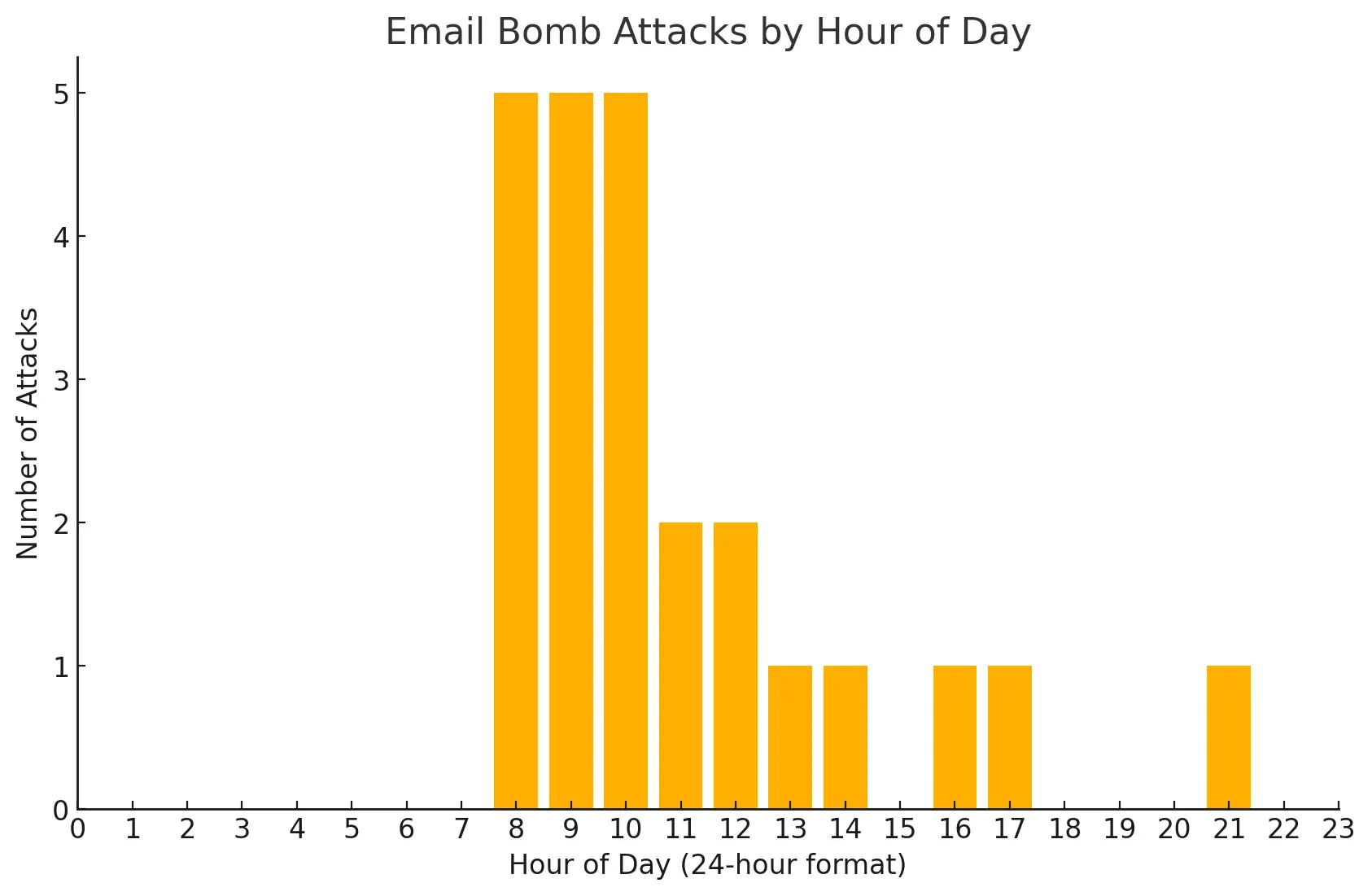

Next, we wanted to understand if certain days of the week and hours during the day were more likely to be chosen for an attack. Our analysis shows that half of the attacks occurred on Fridays, possibly to maximize disruption ahead of the weekend. Attacks on other days were much less frequent. Notably, no attacks were observed on Saturdays or Sundays, aligning with the operational patterns of many organizations.

Attacks most frequently began during the 8:00 to 10:00 window (5 attacks each hour), potentially to overwhelm victims at the beginning of the day when they're likely to check their inbox.

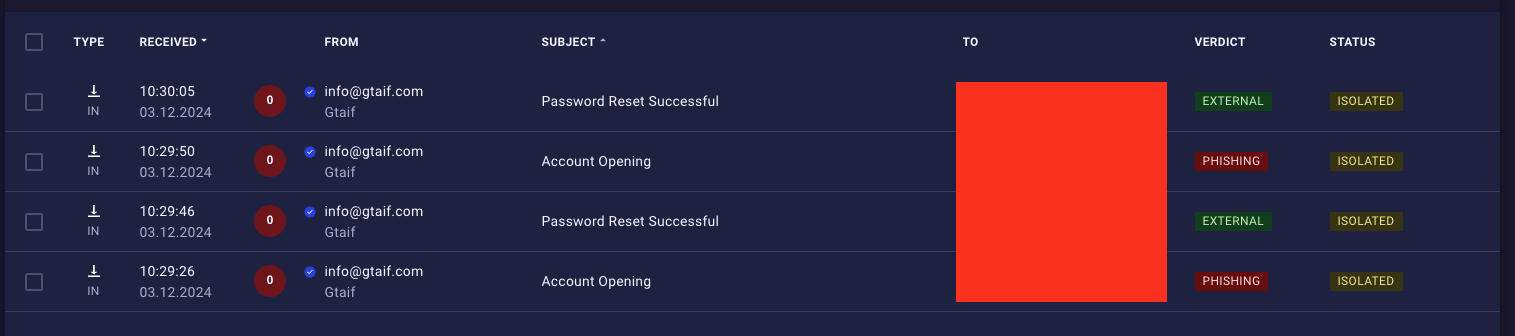

Roughly 90% of the emails in our dataset originated from non-personal addresses, such as 'noreply@' or 'news@', often tied to legitimate newsletters. In some cases, attackers exploited legitimate services to create user accounts or reset passwords, flooding victims’ inboxes with the notifications that follow such actions.

This reliance on legitimate services complicates mitigation, as distinguishing malicious activity from genuine email traffic is difficult.

Attackers create user accounts and reset passwords to flood inboxes. Screenshot taken from the message list inside xorlab email security

In some instances, we were able to discover the account profiles created by the campaign (the fact that some services expose this information to the public is a topic for another discussion). Obviously, the attackers only cared about the validity of the email address; other than that, we did not find any other personal identifiers.

Publicly accessible member profile of one of the victims. The profile lists the email address (file edited to hide personal information)

Our analysis suggests these attacks were likely linked to an email-bombing-for-hire service. Attacks either lasted about one or two hours. The two exceptions that ran shorter could point to tests at the beginning and in the middle of the campaign.

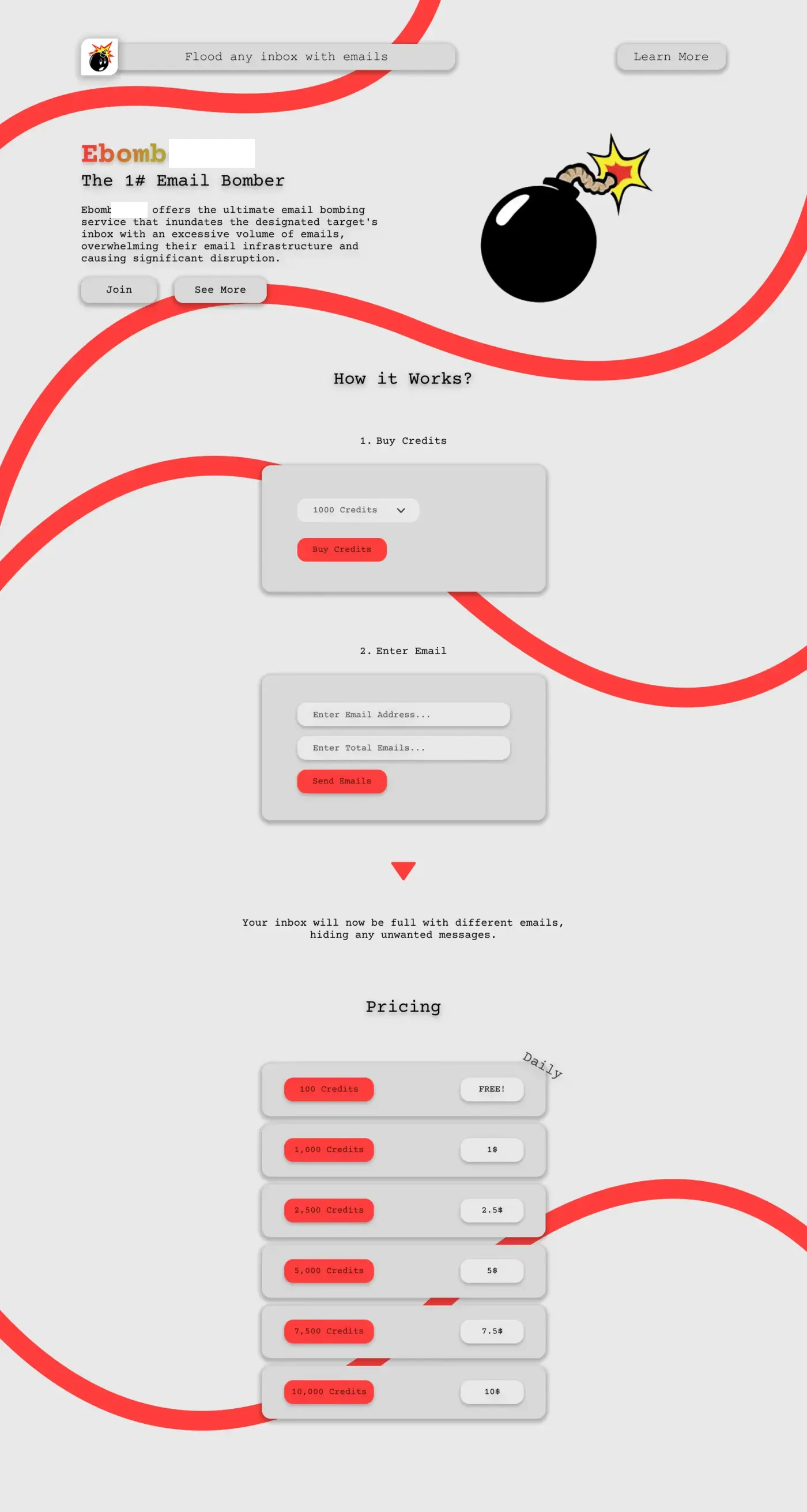

There are many email bombing services available and it is not possible to identify for sure which one was used in this attacks. Through a quick search on dark web forums, we were able to find a service that sells 10,000 credits for $10 and enables bad actors to easily bomb target inboxes with up to 18 emails per minute.

Maybe coincidental, this exact service upgraded to version 5 on October 16, in the middle of the campaign. It could explain (again, this is speculation) why we observed an increase in email volumes mid November and why we saw a gap in activity mid October to mid November.

Screenshot von der Website eines E-Mail-Bombing-Dienstes. Datei bearbeitet.

While email bombing can serve as a smokescreen for fraud or account takeovers, we found no evidence of such malicious intent in these attacks. Instead, their primary goal appears to be disruption.

However, reports from victims suggest a potential connection to the Black Basta ransomware gang. Some individuals were contacted by IT support via phone or Teams after the attack—a tactic known to precede ransomware deployment. Coupled with the timing of attacks on Fridays, this aligns with Black Basta’s modus operandi.

Email bombing attacks abuse the email notification mechanisms of legitimate newsletters, marketplaces, and other such services. The emails that land in the inboxes are not malicious – they're free of social engineering tactics, spammy topics, and harmful links and attachments. It's for this reason that security teams and email administrators struggle to find the right cure. We've seen people go so far as to change the email address of people affected.

Comment

by u/Alternative_Rush_817 from discussion

in cybersecurity

Others monitor affected mailboxes closely to derive keyword and block lists. But: this takes a lot of time and may not be very effective, especially when the goal is to protect against the next wave of email bombs. Especially keyword lists tend to cause a lot of false positives because the emails themselves are not malicious. Regular password resets, account change notifications, and even newsletters may end up in the quarantine too.

Comment

by u/Alternative_Rush_817 from discussion

in cybersecurity

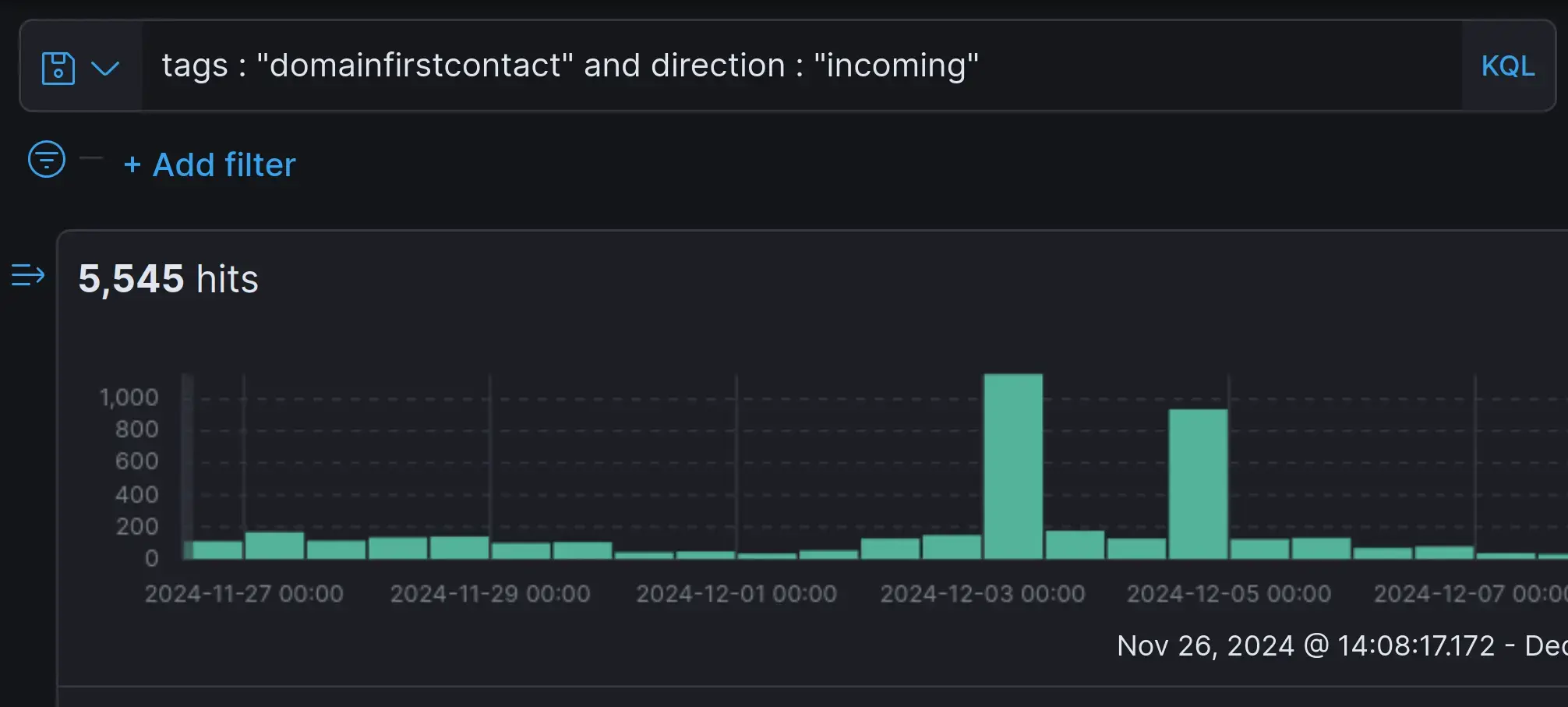

Email bombings typically contain a large number of emails from domains not known to the organization. Searching for this pattern and applying a sense about "normal" volumes allowed us to identify past email bombing waves with high accuracy.

Screenshot: xorlab search pattern to identify email bombing waves in incoming traffic

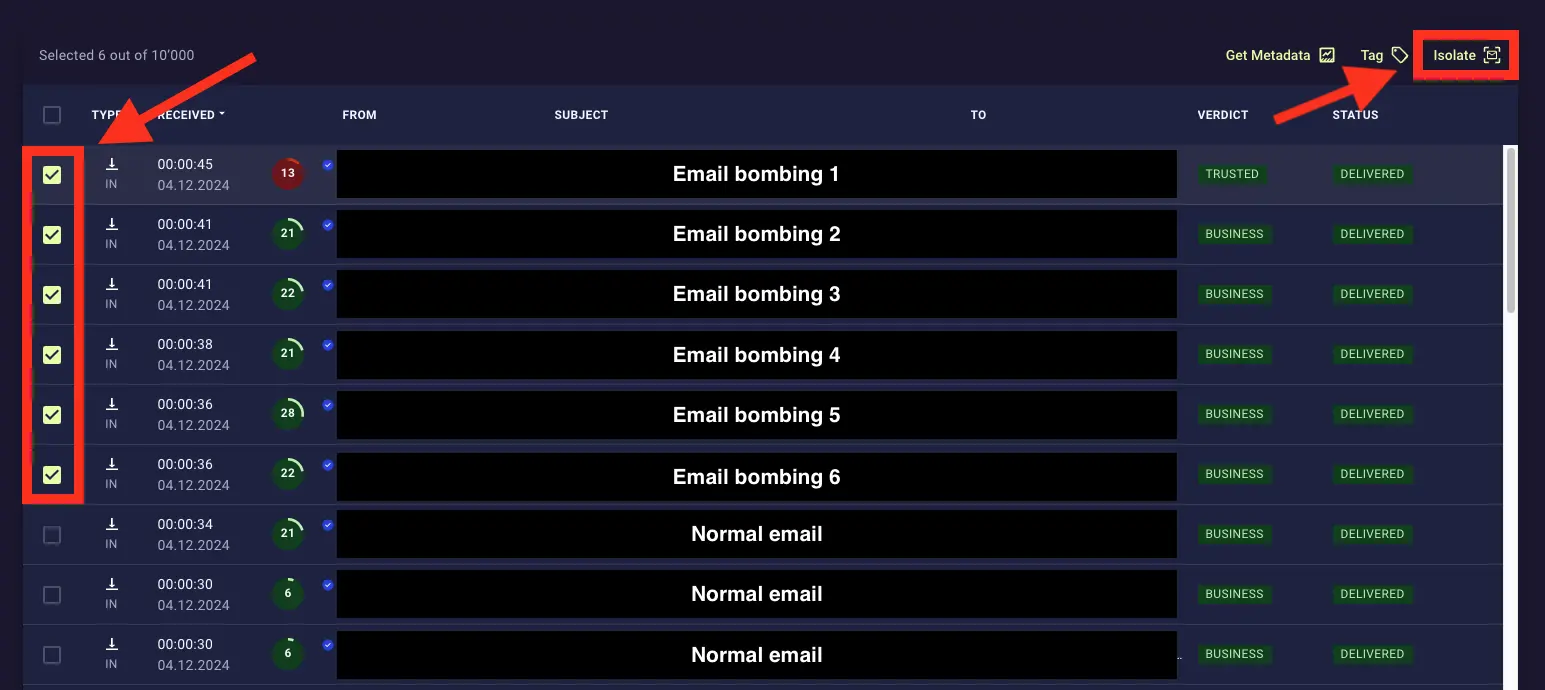

xorlab customers used this query to find all emails belonging to the wave and subsequently remove them from the victims' inboxes.

Screenshot: xorlab's bulk-isolation lets customers remove email bombs quickly and without much effort.

We believe that this simple filter can be engineered further into a powerful detector of future email bombs, something we'll work towards. By setting a threshold on the delivery rate for example, we could quickly detect an ongoing email bomb and automatically block further emails from the wave. Emails already delivered could be isolated automatically based on the anomaly. To avoid that victims receive "regular" newsletters from the services they were signed up to, automatic unsubscribes could be triggered.

xorlab customers already expose victims to more aggressive filtering of auto-generated emails. We've also helped them develop scripts to automatically unsubscribe victims from abused services.

If there's anything that we can learn from email bombing, it's that defenders need a better understanding of how their organization uses email to prevent, detect, and contain such threats. Just knowing that neither the recipient nor somebody in the organization has used a service in the past that is now sending newsletter subscription or account creation notifications makes a big difference.

It's clear that email bombing attacks will evolve. Volumes will increase and attackers will get smarter. Organizations must adopt proactive measures to detect and mitigate these threats, such as enhanced filtering, anomaly detection, and automated cleanup tools. If you like to learn more about how xorlab can help you prevent email bombing and other email-based cyber attacks, contact us for a personalized demo.

Title image created with DALL•E.

How email bombing works Email bombing involves overwhelming a target’s inbox with an excessive number of email messages in a very short time. The...

Threat Analysis team

Threat Analysis team

Recent data by Statista shows that now over a million companies worldwide use Microsoft 365 to facilitate collaboration, improve productivity, and...

Adrian Kyburz

Adrian Kyburz